Cold Dew: The period when grasses and trees turn yellow while Chrysanthemums blossom

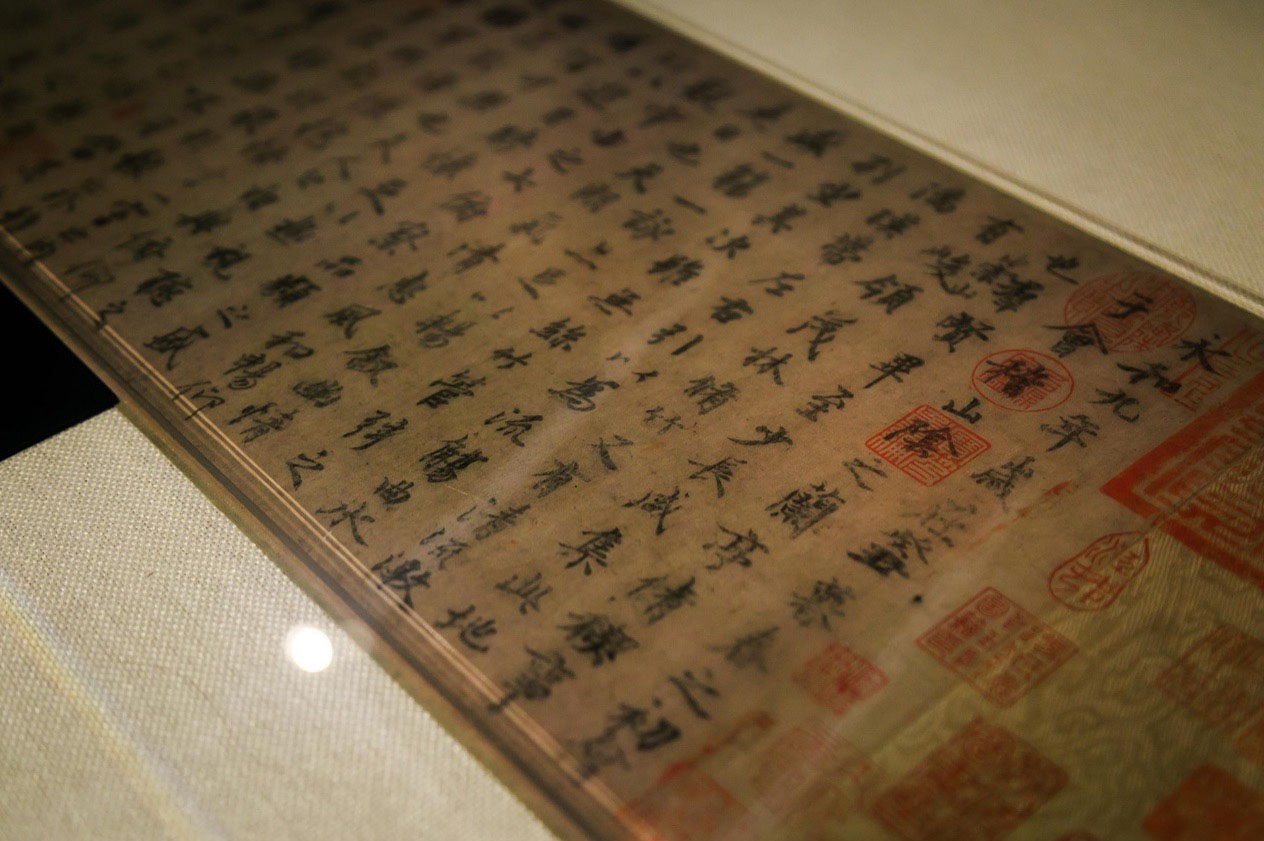

Wang Xianzhi (王獻之, 344-386) was known for his enormous talent. His calligraphy was regarded as comparable with his father, the most famous Chinese calligraphist Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 344-386). They were named “the two Wangs” for their accomplishments in calligraphy. In terms of literature, although Wang Xianzhi did not leave magnum opus like Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion (《蘭亭集序》) as his father did, his proses on beautiful sceneries were also highly acclaimed at his time. In Northern and Southern Chapter of Famous Quotes (《世說新語•言語》) written by Li Yiqing (劉義慶, 403-444), it was recorded that Wang Xianzhi appreciated the spectacular and picturesque scenery of Shanyin county (山陰縣) in Guiji province (會稽郡). He said, “the mountain and the river contend in beauty, making one too busy to appreciate all (山川自相映發,使人應接不暇)”. In the intersection of the autumn and the winter, as what he said, “the transition from the autumn to the winter is particularly unforgettable”, the scenery is even more stunning.This wonderfully precise and rich description of the mountain and the rivers entails the multiplexity of scenery at the intersection of the autumn and the winter. This also reflects the complicated emotion of this gentry in Eastern Jin Dynasty (東晉) on the vicissitudes of the seasons and the quick passage of one’s lifetime. From the perspective of the twenty-four solar terms, the beginning of the intersection of the autumn and the winter begins with the solar term of the Cold Dew (寒露, the translation in accord to the official translation by the Chinese Meteorological Administration). In Annotation on seventy two major features in lunar calendars (《月令七十二候集解》) written by Wu Cheng (吳澄, 1249-1333) in Yuan Dynasty (元朝), it was mentioned that “the Cold Dew is a solar term in the ninth month of the lunar calendar, which is also the date of the festival of the ninth month, when the dew in the freezing air is nearly frozen (寒露,九月節。露氣寒冷,將凝結也)”. The ninth month of the lunar calendar is the fall of the autumn. Different from the “coolness (涼)” at the Beginning of the Autumn (立秋) and the “coldness (冷)” in the Autumn Equinox (秋分), the weather of the Cold Dew is characterized by “the freezing air of the dew (露氣寒冷)”. The term freezing precisely illustrates that this is a stage when dew turns into freezing dew. The character Jiang (將, soon, nearly) is intentionally adopted in the phrase to describe the slow progression from cold to freezing, but not the phenomenon out of a sudden.

This dynamic progression is an extension of the natural trend starting from the White Dew (白露) and the Autumn Equinox (秋分). For example, the first feature of the White Dew is the coming of snow geese (鴻雁來), which migrate from the North to the warmer South. Similarly, the first feature of the Cold Dew is also related to the migration of the snow goose: all snow geese arrive and become the guest (鴻雁來賓). The character Bin (賓) here means guests in comparison with those snow geese which arrived earlier. Ancient Chinese said, “snow geese that arrived before the midst of autumn are the hosts, while those who arrived later in late autumn are the guests (雁以仲秋先至者為主,季秋後至者為賓). The snow geese that arrived at the solar term of the Cold Dew should be the last migrating birds which arrive in the South. In the famous work Farewell Prose written on the Prince Teng’s Pavilion (〈滕王閣序〉) written by Wang Bo (王勃,650-676) in late autumn, it was written that “crowds of snow geese were so afraid of the freezing weather that their loud twittering broke the water surface in Heng Yang county (雁陣驚寒,聲斷衡陽之浦)”. At that moment, the weather during the journey was becoming more difficult. Those few groups of snow geese which hustled to fly southwards evoked the poets’ resonance and lamentation to their own ever-drifting life. Similarly, in the famous work Slowly Slow Song (Sheng Sheng Man 〈聲聲慢〉, a format in Song Dynasty Lyrics) written by Li Qingzhao (李清照, 1084-1155) in Northern Song Dynasty (北宋), she wrote “I saw the snow geese passing when I was so sad. I suddenly recognized them as my old acquaintance (雁過也,正傷心,卻是舊時相識)”.Also, in Crimson River (Man Jiang Hong, 〈滿江紅〉, a format in Song Dynasty Lyrics) written by Shi Xiaoyou (石孝友,?-?) in Southern Song Dynasty (南宋), he wrote, “the crowd of snow geese were afraid of the freezing weather, their sound evoked my sorrow of leaving, which is as much as ten thousand Huk (斛) in volume (雁陣驚寒,故喚起、離愁萬斛)”. These are some of the prominent examples. The Autumn Equinox is characterized by the chilly wind and the old dew (風清露冷), while the weather turns from “cold” to “freezing (Han, 寒)” in the fall of the Autumn during the Cold Dew, when temperature in the morning and the evening is even lower, a forecast of the arrival of freezing cold winter. Therefore, we can see that the ancient Chinese use of the Chinese character Han (寒, freezing) in the naming the solar term Cold Dew in late autumn is definitely not a causal decision.

After the Cold Dew, the cold air from the North become more vibrant when it moves to the south, bringing in winds of the Cold Dew(寒露風)and a drastic drop in temperature. Even in the South of the Yangtze River, the cold current leaves the countryside in a midst of an aura of solemnity. The description of “the unforgettable scenery (尤難為懷)” by Wang Xianzhi (王獻之,344-386) quoted in the previous paragraph is both a eulogy to the beauty of the scenery and a rumination of the ups and downs of one’s life in reaction to the solemnity reflected in the landscapes. This mixed feeling of sorrow and joy is so complicated to be expressed fully in words. From the perspective of phenology, as the weather in the fall of the autumn is becoming much colder, there are some signs from the nature. In China, there is a transition of the descriptions of late autumn from the more ancient quote “a falling leaf lets us know the arrival of the autumn (一葉知秋)” to the descriptions in the lyrics Jade Butterfly (Yu Hu Die, 〈玉蝴蝶〉, a format of Song Dynasty lyrics) written by Liu Yong (柳永, 984-1053) such as “the scenery in the fall of the year is solemn and scattered (晚景蕭疏)” and “the leaves of the parasol tree is turning yellow and falling down (悟葉飄黃)”. This Qi (氣) that brings the solemnity begins as early as in the solar term of the End of Heat (處暑) and is becoming obvious in the Cold Dew. In the prose Nine Quests (〈九辯〉) written by Song Yu (宋玉, 298- 222BC), he wrote “In this desolate season, trees are shaking with leaves falling and gradually withering (蕭瑟兮草木搖落而變衰)”. In Words for the autumn winds (〈秋風辭〉) written by Liu Che, the Emperor Wu of Han (漢武帝劉徹,156-87 BC), he wrote “plants and trees turn yellow and fall down, while the snow geese are heading south (草木黃落兮雁南歸). In the poem Hiking (〈登高〉) written by Du Fu’s (杜甫, 712-770), he wrote “countless woods and plants are falling in a mournful manner (無邊落木蕭蕭下)”. All of these were describing the typical scenery of the fall of the autumn, which echoes with the writers’ lamentation to their life experiences.

In the old Chinese wisdom “Collect in the autumn and hoard in the winter (秋斂冬藏)”, the Chinese character Lian (斂), which means collect, has two different meanings. The first meaning is the harvest of various crops, while the second meaning is that the Qi in the heaven and the earth is now retreated and no longer explicit, which could be represented by the natural phenomenon of withering of trees and plants. In the time when the Qi is turning low, the blossoming of chrysanthemums at this moment makes it special and unique. In Miscellaneous Tales of Hangzhou (《東城雜記》) written by Li E (厲鶚,1692-1752), he wrote, “chrysanthemum is a special type of flower that blossoms at the time when other flowers and trees are withering. While this is the time for retreating, it still stands in an elegant and colourful manner (菊之為物,發於卉木凋落之後,時雖揫斂,而幽姿雅艷).” The third major feature of the Cold Dew is the blossoming of yellow flowers of chrysanthemum. In Annotation on seventy two major features in lunar calendars (〈月令七十二候集解〉) written by Wu Cheng (吳澄,1249-1333), it was mentioned that “all plants and trees flowers at the time dominated by Yang Qi are abundant, chrysanthemum is the only exception that blossoms at the time dominated by Yin Qi (草木皆華於陽,獨菊華於陰)”. The Chinese character Hua (華) means flower (noun) and flowering (verb). Chrysanthemums blossom in late autumn, standing amidst others in the solar term of Cold Dew and Frost’s Descent (霜降) and last until early winter. Therefore, the ninth month in the lunar calendar is also coined as “the Month of the Chrysanthemum”. With the exception of the year with leap months, Cold Dew is the traditional festival of the ninth month (九月節) because it is between the Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋節, the fifteenth day of the eighth month) and the Double Ninth Festival (重陽節, the ninth day of the ninth month). With the beautiful golden scenery of the blossom of chrysanthemum, one could feel the blessing of warmth amidst the whistling of cold wind. Therefore, ancient Chinese listed plum blossoms (梅花), orchids (蘭花), bamboos (翠竹) and autumn chrysanthemums (秋菊) as the “four flowers with virtual characters (四君子)”. Among them, chrysanthemums were widely complimented in the literary works throughout the Chinese history.

The creation of the nature as well as the creativity of ancient Chinese create the Junzhi (君子, persons with virtue and characters) culture that praised the scenery in order to maintain a good tradition which has become the core part of our culture, passing down and sustaining from generations to generations.

Reference

Book

1. 吳澄:《月令七十二候集解》(北京:中華書局,1985年)。

2. 劉義慶著,徐震堮校箋:《世說新語校箋》(北京:中華書局,1984年)。

Journal Article

1. 張文彬:〈寒露風的危害及防禦措施〉,《現代農業科技》,第 16 期(2013年),頁254。

News or Magazine Article

1. 淩鶴:〈寒露驚秋晚 朝看菊漸黃〉,《遼寧日報》,2022 年10月8日,第6版。

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message